January 14, 2017 javascript es6 currying partial application function redux middleware

Currying is named after Haskell Curry, an American mathematician and logician.

Currying is named after Haskell Curry, an American mathematician and logician.

Currying

Currying is the process of converting a function, that accepts n arguments, into a sequence of n chained function calls, having exactly one argument each.

This is best explained with an example, as there’s almost no definition I can come up with that is 100% clear without one. I will re-use the same example throughout this article to (hopefully) avoid confusion.

Let’s look at a simple multiply function. It accepts three operands as arguments, and returns the multiplication of all three as the result.

function multiply(a, b, c){

return a * b * c;

}

let result = multiply(2, 3, 4);

console.log(result);

> 24

A curried version of this function would be:

function multiply(a) {

return function (b) {

return function (c) {

return a * b * c;

}

}

}

The multiply function takes in the first operand, a, as an argument, and then returns a new function that takes in the second operand, b. The resulting function takes in the third operand, c, and then multiplies all three together as normal. The values are all accessible within closures.

We can now call the function in a chain like this:

let result = multiply(2)(3)(4);

console.log(result);

> 24

Right now, we have manually created a curried version of the function. However, in a large application, you won’t want to be doing this. We can create a small curry utility function to do this.

let curry = (fn) => {

return function curryFn(...args1) {

if (args1.length >= fn.length) {

return fn(...args1);

} else {

return (...args2) => curryFn(...args1, ...args2);

}

}

}

The curry function takes in the original function, and returns a function that accepts any number of arguments. We use the rest operator to make reference to all the remaining arguments passed in, as an array. It is equivalent to using [].slice.call(arguments).

If the number of arguments passed in is the same/greater than the number of arguments the function accepts (it’s arity), we simply call the function with all the arguments, and return the result.

However, if there are less arguments than required, we return a new function that accepts any number of remaining arguments, and call the curryFn function again, combining the previous set of arguments and the new set passed in. If the arguments are complete the next time the curry function is called, we call the function and return the result, otherwise we continue until all arguments are complete.

If we take our original example, we can use the curry function like so.

let curriedMultiply = curry(multiply);

let result = curriedMultiply(2)(3)(4);

console.log(result);

> 24

This is similar to how curry functions are implemented in libraries, such as Lodash. However, in the Lodash implementation, it also accepts an optional arity parameter. A function in JavaScript never requires you to define all it’s arguments, and we can access everything via the arguments array-like object. If you don’t declare all parameters, the value of Function.length won’t be useful enough.

It’s interesting to note that, although only one argument should be accepted for each function in the chain, as per the definition of currying mentioned earlier, this utility function actually allows you to pass in as many arguments as you like. See below.

console.log(curriedMultiply(2,3)(4));

> 24

console.log(curriedMultiply(2,3,4));

> 24

console.log(curriedMultiply(2)(3,4));

> 24

Partial Application

Partial Application is the process of taking an original function of n arguments, and generating a new function that fixes some of the arguments, and takes in a smaller number of arguments.

This is similar to currying, and one could argue that currying is a form of partial application. The main difference is that the returned function can have any number of arguments, and the return value is always the result of the original function call, not another function in the chain.

The following function takes in one argument, and returns a new function that accepts two. The original argument is ‘fixed’.

function partialMultiply(a) {

return function(b, c) {

return a * b * c;

}

}

We can now use it like this:

let multiplyBy2 = partialMultiply(2);

let result = multiplyBy2(3, 4);

console.log(result);

> 24

This is actually very similar to how Function.prototype.bind() works.

The bind() method creates a new function that, when called, has its this keyword set to the provided value, with a given sequence of arguments preceding any provided when the new function is called. – MDN

The same behaviour can be achieved with bind as follows:

let multiplyBy2 = multiply.bind(this, 2);

let result = multiplyBy2(3, 4);

console.log(result);

> 24

The bind function is more generic because it allows you to dynamically decide how many arguments to fix. You can pass in as few or as many arguments as you would like. The only problem here is that we have to alter the this binding of the function, which is sometimes not what you would want to do.

We can implement a simple partial function that does the same thing without modifying the this context as follows.

function partial(fn, ...args1) {

return (..._args2) => {

return fn(...args1, ..._args2);

};

}

And using it:

let multiplyBy2 = partial(multiply, 2);

let result = multiplyBy2(3, 4);

console.log(result);

> 24

The main difference in what this function does as opposed to curry is that once you have passed in n arguments the first time, the returned function must receive all the remaining arguments. There is no chaining of the function calls.

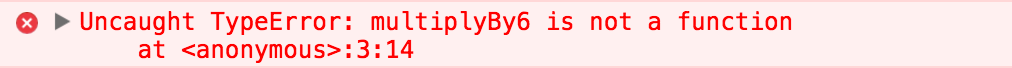

For example, if you tried to do the following, you will receive an error.

let multiplyBy2 = partial(multiply, 2);

let multiplyBy6 = multiplyBy2(3);

let result = multiplyBy6(4);

console.log(result);

Currying in Practice

So far we have seen a crude example of currying with simple math, but when is it actually used in practice? A great example of it in modern front end development is the use of middleware in Redux. I’m not so familiar with Redux myself, but I found a good explanation of the applyMiddleware function, which uses currying and composition. Check out Redux Middleware by Paul Sherman.